January 15, 2025 • Posted by Design Bay Area

This past October during Design Healdsburg, attendees were treated to an inspiring conversation about how landscape architecture + design contributes to the reciprocal relationships we have with the land. We explored how the history of Healdsburg as an agricultural community contributed to its evolution and how it will help the community thrive well into the future. Our featured speakers were all experts in their fields: James Munden of MFLA, Lucas Dexter “The Tree Guy” of Dexter Estate Landscapes and the talk was moderated by Jim Heid who is not only the founder of CraftWork, but a landscape architect who is driven to create authentic places and resilient local economies.

The community gathered in Healdsburg to see first hand how design plays a role in community and while Design Healdsburg took place at different venues all over the town, this event was hosted at Craftwork Healdsburg, Sonoma County’s premier co-working space.

Below is an edited transcript from the live event.

Pictured: Jim Heid and James Munden. Photo credit: Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

JIM HEID: Well, good afternoon. I’m Jim Heid. I’m the owner and founder of CraftWork, where you are today. Thank you all for coming. It’s great to have an event like this in a co-working space that can also act as a forum for informed and intelligent conversations about design, the future of our community, things going, and a place where the community can just come together.

We’re happy to host Design Healdsburg on their maiden voyage in the Craftwork space. We also run a series called Design Dialogues, which we’ve done for 3 years.

This is almost like an acoustic set. It’s going be unscripted, a little more conversational, a little bit of interplay. We had a really fun conversation just the other day with James and Lucas catching up with each other, talking about the profession, talking about what was going to be interesting to share. We’re going to touch on four things: grounding the conversation in a bit of the history and context from a landscape standpoint in Healdsburg, talking about the role of a landscape architect and how much the profession has evolved. It’s been interesting to watch the profession become a real force in discussions about the built environment. Then we want to talk about what a rural environment means and why Healdsburg is such an attraction for people? And then finally, the relationship we’re having with the land here in Healdsburg.

We will be speaking to James Munden and Lucas Dexter and I’m going to steer the conversation as the moderator. I think I got tapped because, aside from CraftWork, I also have a landscape architecture and development background.

We’re going to touch on four things, grounding the conversation in a little bit of the history and context from a landscape standpoint of Healdsburg, talk a little bit about what is the role of a landscape architect and how much the profession has evolved.

I’m probably a lot older than you both, but when I went to school, I don’t think there was anybody in our program that actually selected landscape architecture as a profession. They all kind of discovered it somewhere along the way.

And then we want to talk a little bit about what a rural environment means and why Healdsburg is such an attraction for people? And then finally, the relationship that we’re having with the land here in Healdsburg.

Pictured: James Munden. Photo credit: Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

How you got into landscape architecture, what your focus is, and what you love about the profession?

JAMES MUNDEN: Thanks, Jim. Well, firstly, I’m just really excited about being here with you, Jim, and Lucas. It’s a great opportunity to be part of Design Healdsburg and talk about the profession.

I’m from Southeast England in Kent, specifically from a small village, called Wootton. It’s a rural area, a lot smaller than Healdsburg, but it was the beginning of my interest in being out in nature.

I did a lot of gardening when I was younger, working on private residences and on local farms as a Summer job. My dad and stepmum own a beautiful property in the village, a gardener’s cottage on a piece of land where a brick walled garden stands, dating back to the 1800’s. It created this fascination in me about secret gardens and the intimate spaces they create. It was a place you discovered, and it really piqued my interest in doing something around landscape and nature. As I got older, I found out about the profession from a friend of mine, Henry, who suggested Landscape Architecture would be a good fit for me.

So, I learned more about it and did my BA Hons Degree and postgraduate diploma in Landscape Architecture. After that, I just wanted to get out of the UK to explore and travel the world. On my travels, I met my wife and she was from San Francisco. After working in London on quite a few interesting urban regenerative projects, we moved to San Francisco and I started to work in the Bay Area. I had the fortune of working with Lucas and his dad, Dave Dexter, on some great projects back then.

I started working with my business partner, Marta Fry, a few years after I moved to the Bay Area and about 5 years ago, ended up here in Healdsburg. I’ve really enjoyed working on a variety of project types that include private and public urban spaces on one end of the scale, and rural private estates and public hospitality projects on the other. But today, we’re going to be focused more on the rural side of landscape.

Pictured: Lucas Dexter. Photo credit: Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

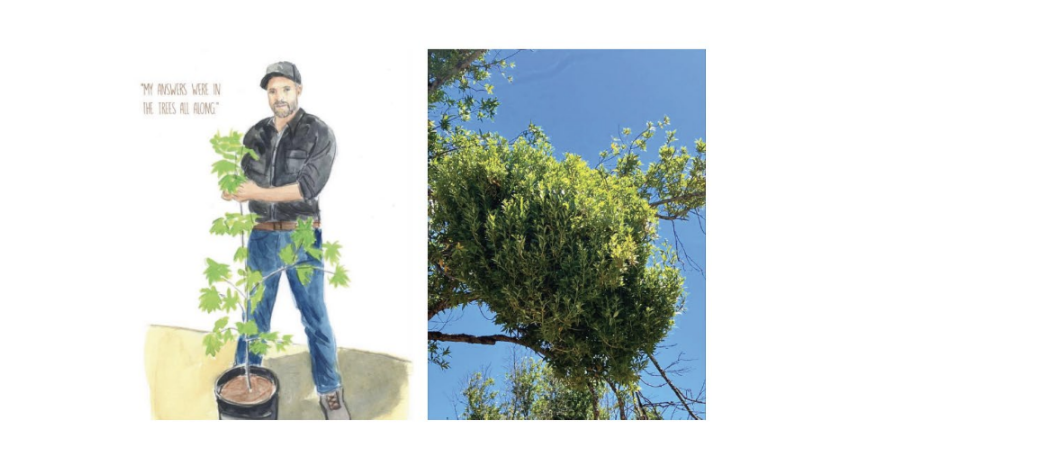

JIM HEID: One of the great things about doing this, is you get to meet people you didn’t know. So I didn’t know Lucas until this Wednesday and when we finally got together, I learned about his story and the incredible work he’s doing. He has been included in Amy Stewart’s most recent book ‘The Tree Collectors’, so you can tell us a little bit about this book and your background.

LUCAS DEXTER: Thank you, Jim. I appreciate it. And such a great space. And thank you, James, for getting me involved.

I have a different exposure to design because I’m a 2nd generation landscape contractor. So we build large scale gardens with all sorts of different landscape architects and a variety of styles. I’ve been doing it for over 20 years.

My dad started in 1985, and he’s still around helping, so I’ve seen it from a contractor’s perspective. We don’t have a design element to our company, we only work with architects but we’ve seen a whole spectrum of types of plans and projects over the years.

JIM HEID: Luke, you said something really interesting when we were chatting the other day, that you won’t even take a job unless somebody shows up with a set of plans.

LUCAS DEXTER: Correct. That’s the barrier to entry to work for our company. You have to have landscape architecture or design plans in hand.

And through that, I’ve also got into plant collecting and growing trees. With collecting trees, you want to find the rarest one you can and I’ve been introducing new plants to the area, which we’ll get more into a bit later.

I was born and raised here in Sonoma County. I’m from Sebastopol, so Healdsburg has always been on my radar and I’ve been here doing projects and enjoying Healdsburg’s evolution over the last 40 years.

Pictured: Craftwork Healdsburg. Photo credit Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

How has the history of Healdsburg as an agricultural community contributed to its evolution?

JAMES MUNDEN: I think we’re really interested to talk about how agriculture has influenced the city and how it’s going to continue to evolve. So we’ve got some slides that touch on some of the history. I’m going to talk about it fairly quickly. There’s so much info, but if you are interested, check out the Healdsburg Museum website. Really fascinating. Such a lot of great photographs on there.

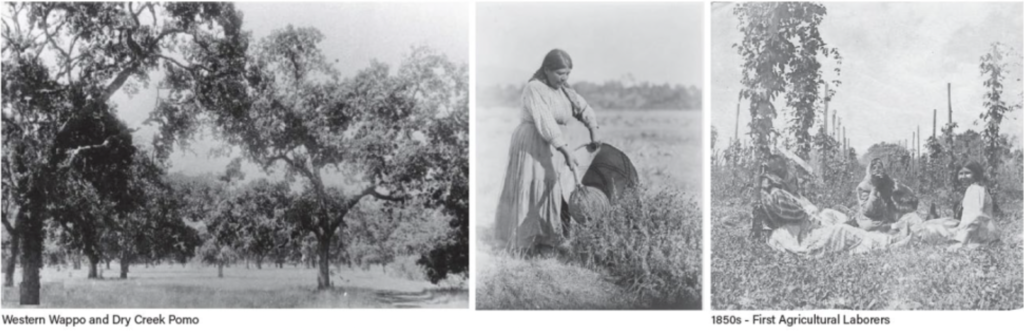

The indigenous WAPO tribe were originally here and they managed the land in such a way that we can hopefully get back to and learn from.

Credit: Healdsburg Museum

They used fire and various methods to cultivate the land in ways that we’ve since lost in some ways. Interestingly, back in 1850’s, gold miners that turned into more agriculturalists started to modify the land to work with certain crops. After initially removing a lot of the indigenous people from the land, they brought them back on because they were the ones who really knew how to work the land. Unfortunately, the WAPO thrive weren’t volunteering and were taken against their will to do the work but their positive influence on the land was valuable. The photograph on the right is a group of indigenous women who are in a field of hops. So originally, vines were being grown, but there was actually a lot of hops alongside hay, wheat and fruit trees. It was quite a diverse collection of produce and crops.

Over time, the farming practices brought more people to the region and they started to consider the need to create a place to settle. It was Harmon Heald, who was the one who is considered to have founded Healdsburg as a settlement. Back then, it was very much a place for the people that worked here. Slowly the area grew to have a post office and a general store, but it was mainly to service people who worked and lived here. There weren’t that many people from different areas coming in. It was catering for the locals.

The railway tracks were then built, which really helped with trade and influenced a lot of the produce that was being grown here. Pictured, is actually one of the last, native, Madrone trees that was in the plaza, before it was removed. Originally, this whole area was oaks and madrone trees, but, over time, they were removed. As Healdsburg got more and more popular, people did start to come visit.

Madrona Tree 1870. Credit: Healdsburg Museum

In the early 1900’s there was a water carnival, which took place on the edge of Russian River near Memorial Bridge which became this amazing center of attraction to the area. People came from quite a long distance to experience and enjoy it.

Water Carnival/Harvest Festival 1946. Credit: Healdsburg Museum

In the early days, you had many of the original native trees in the plaza, but over time, they got removed because of the needs of access for the horse and cart. Apparently, wild pigs were a big issue, which was the original reason behind the fence built around it, just to keep them back. And then, eventually, they realized that the trees were declining, so they removed them. And then it became a little bit of a free for all. They started to put in cedar trees and someone had the idea of making them into topiary balls, which, you know, in this case, thankfully, I don’t think lasted for very long.

Credit: Healdsburg Museum

They didn’t provide much shade or any kind of relief from the climate. Too much maintenance. And then, over the years, there’s been other trees planted- the date palm, redwood trees which some are still here today.

As a landscape architect, we are always talking about what makes a good public space and trees are an important part of that for shade, but also, for spatial organization.

JIM HEID: I always think of the Healdsburg plaza as the town’s living room, and it has a lot of volume, as the biggest room in town when you don’t have that much landscape there. Historically the plaza seemed to be overpowered by the landscape.

As a landscape architect, I wonder, is it time to start editing a little bit in the plaza so that you can get that sense of more open space and a play of shade, shadow and light?

JAMES MUNDEN: Exactly. I think that’s getting into the idea of balance as a landscape architect. You’re constantly dealing with that balance between nature, vegetation, and hardscape and what’s the real purpose of that space.

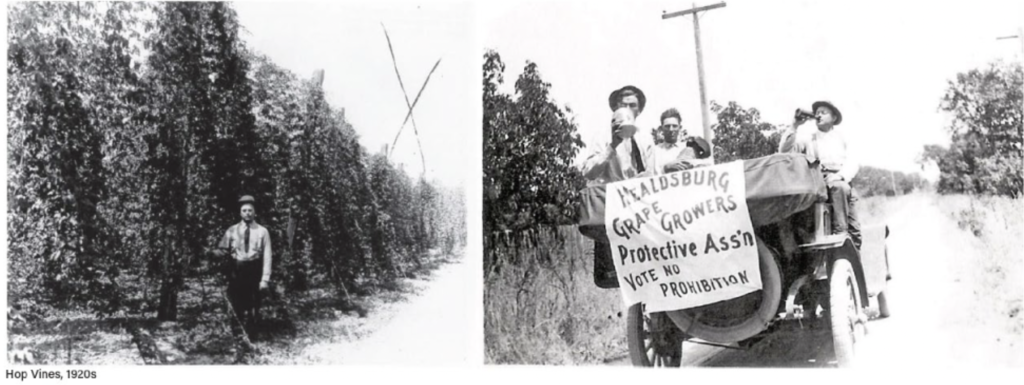

To fill in some extra gaps historically for the area, much of the purpose of the land at this time was growing crops, specifically hops. Apparently, Healdsburg was one of the biggest areas for hops in California at one point until prohibition began.

Credit: Healdsburg Museum

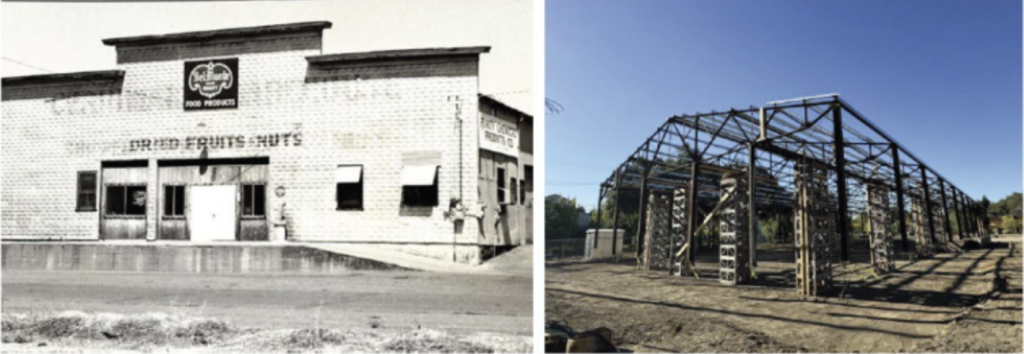

As the production of hops and grapes slowly declined due to prohibition, there was still a lot of grapes being harvested in secret. The Foley Community Center building, that’s currently being renovated as the new site for the Farmer’s Market, was a bit of a cover up location for storing grapes and shipping them out without anyone knowing.

The crop that eventually took the grape’s place, as a result of prohibition, was prunes, making Healdsburg known as the ‘buckle of the prune belt’. When you drive out into Alexander Valley, we now see lots of grapevines, but it used to be all plum trees, and in the springtime, people used to come from all over just to see all the blossoms and mark that seasonal moment in time.

So, it’s important to note that we are talking about how agriculture has influenced Healdsburg and how it still influences Healdsburg today.

Whether it’s a horse and cart or the modern-day tractor, this town is heavily influenced by farming. That’s a big attraction for people to be up here and experience the local food that comes from the land.

Credit: Healdsburg Museum (left) and MFLA (right)

The building I mentioned earlier (The Foley Community Center), is being renovated and the likes of TLCD Architects, Alan Cohen and Andrea Cochran are involved in the design. It’s taken 15 years or so to break ground, but they are using the old structure, very pared back, and renovating it for the Farmer’s Market, which currently happens every Saturday morning in the parking lot across the road. This allows for an important community resource, the opportunity to have all year-round space. The Farmers’ Market is such a critical part of why people love being up here.

Some of you might be going to Flowers Winery, as part of Design Healdsburg’s event offerings, which is not too far from here. A great space that’s been renovated utilizing some of the original bones of the landscape. Hotel Healdsburg has Andrea Cochran’s work with her beautiful courtyards and outdoor gardens.

Some work MFLA have been involved in up here are Silver Oak Winery and Merriam Vineyards which have that agricultural component to it. Even though they are, strictly vineyards for production and tasting, there’s a big positive emphasis now on embracing nature in ways which wasn’t happening back in the 1900’s. So the indigenous knowledge is being utilized in farming practices to be more caring with the land but also improve the crops sustainably.

So that was a bit of a fast history lesson and I wanted to go through and set the scene for our next question.

Credit: Marion Brenner (left) and Joe Fletcher (right)

How do Landscape Architects think?

JIM HEID: For part 2, we’re going to talk about the role of landscape architects. Whenever I talk to students in the architecture, it’s a lot about the object. It’s about the building. It’s about how it sits. It’s the vignettes that you see.

I think landscape architecture by and large, is really about systems thinking. It’s really about how those objects and humanity fit within a larger system.

This is an image that I included because it’s good example of when we used to hand draw, back in the day. It shows a program that was done here in Healdsburg in 1982, with what was a seminal inflection point for Healdsburg.

JIM HEID: Healdsburg was actually on its knees with the square largely boarded up and businesses that you wouldn’t necessarily want to visit. People wouldn’t go down into town. The whole town had been declared a redevelopment area because of the blight. So, the town brought in the AIA to do one of their studies which is now called an SDAP, but it was called a RUDAT at the time.

One of the things that came out of that study was this diagram, which I love, because it really summarizes the essence of systems thinking and what is so unique about Healdsburg. You see the Russian River, the iconography of Fitch Mountain, which is a landmark that you see wherever you go around town, and the footprint of the human settlement in the urban form that is so unique to Healdsburg.

One of the things about Healdsburg that makes it incredibly unique, is it’s the only town along the 101 that is not divided by the 101. Every other town suffers from being split by the 101. And we were spared that, which has allowed us to have a very compact form that fits into this landscape with a boundary of a man-made edge on one side, the freeway, and a natural edge of the mountain and the river on the other side.

JAMES MUNDEN: That is a good segue because it touches on how landscape architects think since it can be hard for us to not think about the bigger picture. Nothing lives in isolation. Architectural elements are within the landscape, but the landscape boundaries are very blurred and it’s hard to know where they start and end.

Image Credit: MFLA

JIM HEID: A funny story about that. One of my mentors early in my career, he used to teach at NC State, and he was a really big thinker. The urban legend was, he got hired to do somebody’s back garden and he did a master plan for the state of North Carolina. It just kept growing and growing because he couldn’t get out of that system.

JAMES MUNDEN: Yeah, clients don’t always appreciate that though. They’re like ‘Hang on, we’re only actually working on this small plot here’.

JIM HEID: That’s what we call ‘Scope Creep’.

JAMES MUNDEN: Yes, ‘Scope Creep’, exactly.

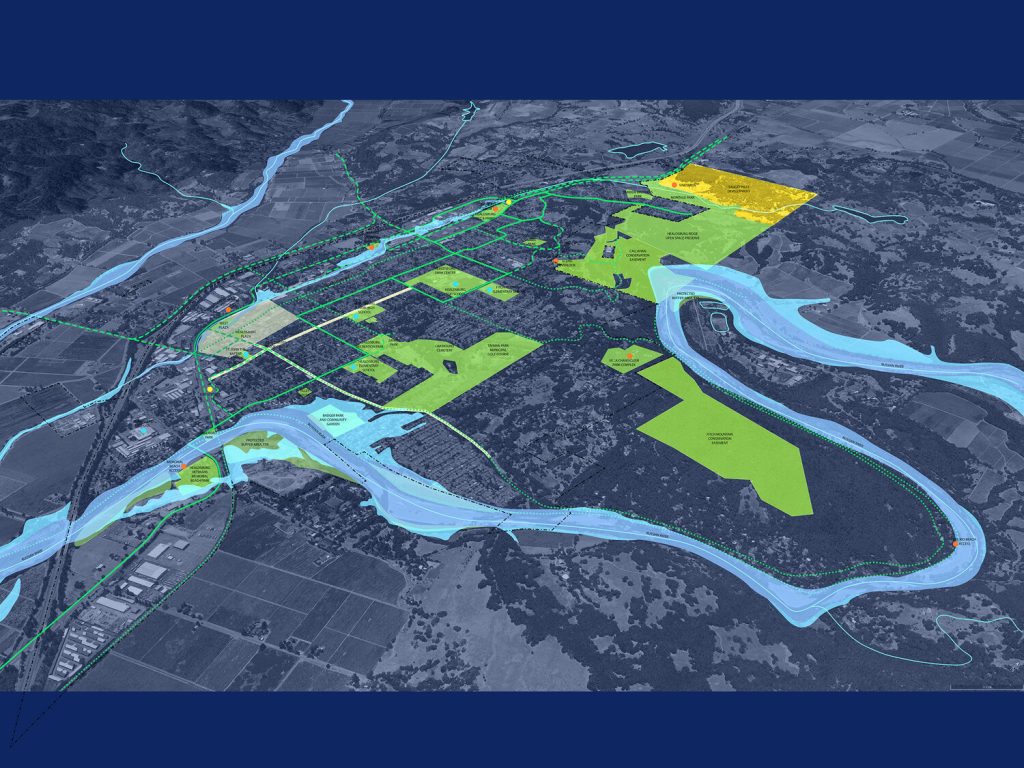

I want to make sure that we talk about the connectivity plan that David Fletcher’s Studio is involved in here to help show how landscape architects think about a large area. This is one of the biggest master plans approaching the connectivity of the city and how it starts to link all these amazing natural resources like the Russian River and the open spaces that already exist but maybe aren’t as easily accessible. I’m not sure of the timeline, but it’s in motion. So, for all of you that keep visiting Healdsburg or for those that live here, it’s going to be an exciting evolution.

Credit: Fletcher Studio

JAMES MUNDEN: So let’s dive in specifically to how landscape architects think and start the process on a project. Similar to architects, things often start with a pen and paper, sketching. Often, you’ll have a client that has a particular brief and a landscape that you’re working within. We’re constantly thinking about how different pieces within a site, which may seem to be very separate, are organized together and how could they be organized in the future. It’s like these puzzle pieces that one is trying to shift and move around to create and make sense of. Personally, in my practice, we are often doing diagrams and spatial analysis to really work out what is the best fit.

The design process I don’t think ever finishes, even when things get built.

With many great landscape architects that you work with, Lucas, would you say you’re sometimes a reality check with some of the ideas that come to you?

LUCAS DEXTER: I’m fortunate enough to work with some really good landscape architects, like yourselves, and a lot of the plan is thought through because of their experience. But, nature will throw things at you that wasn’t planned. Maybe there’s a hotter or windier spot than we thought. So, editing and time will tell you what the garden really wants.

JIM HEID: Do you also find out when you’re doing an install that there are opportunities for a vista or a framing that triggers rethinking a piece of the design?

LUCAS DEXTER: Yes, that happens. I personally may not notice, but we have the landscape architect come out and be like, “That needs to move…and I know you planted it 3 weeks ago, and I know that you’re going to need to bring a crane back, but we need to do this for these reasons.”

It may not be framing correctly or it was different in 2 dimension than it was in person. And then you have the seasonal shifts and the light may be coming down at a different angle. It may be the most crucial time of harvest or we wanted to show a part of the winery in a different light. So, changes do happen.

JIM HEID: Yeah. Well, I think that’s part of the nature of landscape because, again, with architecture, you have a relatively defined or confined environment that you’re working with. You’re borrowing distant views and landscapes that are harder to recognize in 2 dimensional plans and then you may see an opportunity as it’s being built.

I’m sure that the better firms you work with, designers can envision that.

LUCAS DEXTER: It’s impressive what good landscape architects do and how much thought they put into what things are going to be like 10-15 years in the future.

I don’t think people really appreciate that. They say, ‘why can’t I just hire a contractor to just install plants? These are the plants I like. This is what I want to do.’ They don’t understand what they’re missing. It’s really that thoughtfulness about the future and about how the plants are going to interact. It takes experience. It takes somebody to have grown something and to know what it does. What is the max size of that plant? How close are we planting them together when they’re only in 4 inch or 1-gallon containers?

So, I highly suggest when you’re trying to map out your garden to talk to a professional that knows what they’re doing.

JIM HEID: There must be preferences from clients to have the immediate impact versus watching it evolve over time, being part of that evolution as it grows and fills in and watch nature do its thing. Do you find clients appreciate that journey of the 10-year evolution?

LUCAS DEXTER: Some. And then we have some clients that say, ‘I don’t even buy green bananas. I need this done now and it’s got to be a finished product.’ When you’re talking about the size of plants, you’re just talking about time. A 1-gallon to a 5 gallon is typically a year. 5-15 gallons is another year, depending on what plant we’re talking about. With trees, the bigger the box size, you’re buying years of growth. So how many years of someone else’s time or a plant’s time are you willing to pay for? Some people want 140-year-old olive trees or fully mature, large as they can, oak trees. It’s money and a time factor.

JAMES MUNDEN: This reminds me of the conversation we had the other day, Lucas, about the value of a tree. You mentioned something you noticed when you first started working with your dad going on-site.

LUCAS DEXTER: Yes, I noticed on the 1st day on the site there was no real appreciation for the existing native trees. Around 23 years ago, when I started, you didn’t have protection around those trees.

On large scale job sites now, that’s the first thing that happens. The general contractor comes in and fences them off. Sometimes they’ll even strap 2×4’s to the trunks in case someone swings a machine and damages the trees.

Although there is complexity with this kind of strategy when you get into fire protection. About 10 years ago was the first time I had seen 2×4’s strapped to oak trees throughout the whole job site, with tight access and machines in there, which I hadn’t seen before. So I called the superintendent once the job completed and I said, ‘I just want to say I was really impressed with what you did over there with protecting these native tees and hadn’t seen that done before.’ What I didn’t realize was the whole site had burned. And he said, ‘Yeah well, those 2×4’s on the trunks weren’t perhaps the best idea when the fire was coming, because all the trees died.’

So, there’s a balance and understanding that needs to be thought through considering the many conditions on site. We can do the protection but perhaps we take them off in case of a fire. It’s more complex.

JAMES MUNDEN: The value of landscape, thankfully, is becoming more appreciated. When you start to replant, especially with oak trees, it can take so many years to grow to maturity, often, 1 or 2 lifetimes.

LUCAS DEXTER: To get a big old oak tree with a 4-foot wide trunk from Corning, where they were planted over a 100 years ago, is fairly affordable. It’s less than $10,000 usually to get one to Healdsburg in the ground. The reason is there’s less value for larger trees up there.

They don’t climb trees or shake trees to get the fruit out as much anymore. They’re doing high density rows like vineyards and they’re machine picking olives, so there’s not as much value. They want to bulldoze those orchards and put in almonds or something real thirsty, which is frustrating. So for a 120 year old olive tree, you are paying less than a 25 year old oak tree. A nursery grown oak tree that is 25 feet tall, you’re up into 15,000-$20,000 already. I just find it very frustrating that something so available and native, like an oak, is expensive to get something of size. Hopefully, we can disrupt that and get more oak tree nurseries going. There’s a lot of money to be had there.

JAMES MUNDEN: You have to invest the time.

LUCAS DEXTER: You pretty much need land, water and time. And if you have those three things, you probably don’t have a financial problem already. But it’s a good retirement investment, and I think more people could be doing that. They don’t take a lot of water once they’re established, the trees are resilient.

JAMES MUNDEN: On the topic of water, landscape architects need to think about those key resources and how we keep it within a closed loop system.

I was lucky enough to have worked with Silver Oak Alexander Valley Winery, where they had the vision and the money to invest in a winery that is zero net water and energy, in a traditionally very thirsty monocultural industry.

Working to create that closed loop system with infrastructure to clean existing water sources like wells, a natural retention pond and rain collection allowed for efficiencies that supported the eco system as opposed to pulling from it. Same with utilizing the sun’s energy. It’s really critical with landscape design that we are making sure that everything we do has a knock-on effect. Planting, biodiversity, soil health, all contribute to improving a situation, not making it worse. I think it’s critical in a farming context.

You hear lots of stories about the degradation of water + soil in agricultural areas and thankfully there’s a lot more consciousness around it with some laws in place to support the environment. As landscape designers, we’re very much thinking about it day to day.

To finish off this section on how landscape architects think and approach projects, we need to talk about beauty. As designers, we want to make beautiful things. Biophilia is a term that’s being used a lot more now which is related to working with nature and being a part of nature. How does nature influence design? How does it help create relevant design?

Credit: MFLA | Photographer: Joe Fletcher (left) + Patrik Argast (right)

The image here shows the entrance to the tasting room at Silver Oak Winery. There’s a combination of architectural form and nature coming right up to its doorstep. The added complexity of fire is a topic to be considered in all of this. The use of water, the reflectivity, the cooling effects, the climate modulation, they’re all factors which can be very beautiful if they’re done in the right way. I do strongly believe that if it’s beautiful, you’re more inclined to look after it and save it for future generations.

LUCAS DEXTER: If you haven’t been to the Silver Oak location in Alexander Valley, it’s incredible. I will just go there sometimes and drive that entry experience with the flowing grasses and you feel the calm when you get there, it’s just so well done. I really like that project you did.

JAMES MUNDEN: I appreciate that. And to be fair, Lucas wasn’t the one who actually built it.

LUCAS DEXTER: And it’s still good! [laughs, audience laughs]

JAMES MUNDEN: To get this kind of project, the client has to have that vision and be committed to take it along that journey. A project like Silver Oak takes a lot of investment of time and money, and not everyone is able to do that. I think part of the conversation is, how does that start to change in the future, so that some of these groundbreaking, innovative designs enable smaller projects to implement strategies for positive change.

JIM HEID: It’s creating awareness around ideas that people didn’t think was possible in certain contexts. Also, just building the capacity in the industry to do some of these things. Somebody needs to push boundaries.

What is rural and why do people want to visit and live in Healdsburg?

JAMES MUNDEN: Jim is from Sebastopol and been here for 20 years or so and me for 5 years and things have changed a lot in that time. It was all about being the Redwood Empire at one point in history and most recently, wine has been the latest chapter. With an increase in tourism, what is the draw to visit Healdsburg?

LUCAS DEXTER: And with an increase of tourism and new developments it’s all exciting, but important to have a balance and sensitivity to the needs of both residents and visitors.

JAMES MUNDEN: There’s a kind of release when you come up here, especially when you are living in a place like San Francisco or a built-up urban environment.

LUCAS DEXTER: Why does it feel more comfortable here than going from the city to a Marin rural town which doesn’t have the same relaxed feeling as here?

I love Marin, but there’s a different intensity there. Here, I just feel a little bit more space, relaxed and grounded.

JAMES MUNDEN: Maybe it’s more about the distance, right? The distance it takes to come up here, it’s a bit more of a commitment.

JIM HEID: Yeah. The decompression of the trip. Whenever we used to drive up from San Francisco, where we lived at the time, there was that point in Petaluma where the cows are on the left near a barn. It’s kind of the doormat to entering the country. It was always the place where you just felt relief.

JAMES MUNDEN: My parents-in-law had a cabin up on Ida Clayton Road, in Alexander Valley near Saint Helena. My family used to come up for the weekend when we lived in San Francisco, and there was a certain moment after bypassing Healdsburg city center and traveling the windy road of Highway 128, you got to this bridge, which I called the ‘Minty Bridge’. It’s got this minty flavor to the paint and I just thought, ok, I have arrived.

Anything I was thinking about before just dissolved and that was the release. It just calmed me and then I didn’t want to go back. Then Sunday night rolls around, you’re like, ‘well, maybe we could stay Monday’.

Credit: MFLA

JIM HEID: I love this image because it’s a very evocative place for me too. It’s that juxtaposition of the agricultural landscape against the native landscape.

JAMES MUNDEN: This next image gets to that point:

Credit: MFLA

JIM HEID: Yes, it’s that contrast. It’s still landscape. It’s still a working landscape.

JAMES MUNDEN: Right. It’s the straight lines with the natural forms of the hills and the vegetation, which, from a landscape design standpoint is often what you’re trying to achieve. The balancing act between the articulation of the built form with nature softening the edges.

I think the other reason I wanted to show this image is the seasonality aspect where the vines are starting to turn yellow. I think when you’re in the city, especially on the West Coast, the seasons aren’t as expressive as the East Coast or in England, where I’m from.

So living in a rural area, you feel more connected to the seasons, which is a really important aspect of being part of nature and being human. This is definitely a pull towards an area like Healdsburg.

LUCAS DEXTER: Yes, that’s our fall color. We have it in the grapes and there’s one oak that turns yellow and the big leaf maple goes yellow. Other than that, we got the vines.

JAMES MUNDEN: We also have the blossom from the ornamental pears, plum trees and Chinese Pistache. There is also this barn along Hwy 128 which shows markings on the side dating back to 1947 from past floods. The archetypal barn has become the inspiration for a lot of architectural, modern designs to maintain that rural vernacular as part of the visual language in Healdsburg.

Front Porch Farm has a strong presence at the farmers market and is a great example of a farm that takes advantage of the fertile land in the area, while bringing diversity into their practices. There are many others doing a similar thing, most of them are organic, biodynamic or regenerative.

LUCAS DEXTER: Healdsburg kind of skipped the ‘we thought we were Tuscany’ thing. There’s not a lot of Spanish roof tile buildings here. You go to Napa Valley, and there are remnants from the 1980’s & 90’s that were very Tuscan.

Healdsburg is quite special in the way that they kept the agricultural farm vernacular though the years, despite trends.

Pictured: Jim Heid, James Munden, Lucas Dexter. Photo credit: Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

JAMES MUNDEN: That’s true. The Silver Oak client, David Duncan, was very clear about not wanting a line of any trees that resembled Italian Cypress. He said ‘We’re not Napa’. When visitors entered, he wanted them to feel they were driving through an agricultural landscape to really experience the vineyards as they were. He didn’t want to trick it out with extra bells and whistles that didn’t feel authentic to the place.

So, to sum up this section about what it means to be rural in Healdsburg. We have the Russian River which offers opportunities for swimming, riding bikes, walking the dogs, the state parks being close by. The benefits of having a bit more land, allows people to grow their own food, while the warmer weather offers outdoor dining & living. All ways that, we as people, can have a closer relationship with the land and enjoy being up here.

JIM HEID: I’m going to be little provocative on this. I think you’re right, there is this evolution of not trying to be Tuscany, which is good, but I find our downtown streetscape, which has really come out of that study in the eighties, to be fairly pro forma.

What could we do that would make that plaza and downtown feel like you were in Sonoma County? What could we do to the landscape, the streetscape there that would actually make it feel much more regional. Currently, it reflects a time when I was growing up, that you planted the miracle 25 plants that worked everywhere. Perhaps this needs to be rethought with more native, drought resistant plants in mind?

LUCAS DEXTER: We have redwood trees in the square, right?

We had a group of landscape architects from Australia visiting in the Spring, and we took them on tours. We took them to this one incredible site, but they weren’t looking at the house, they just couldn’t believe the forest of redwood trees. They’d never really seen that before, so some people have never seen redwood trees like that in a town square which is special.

JIM HEID: If you drive the streets of Healdsburg, what I really notice is those exclamation points of the redwoods that peek up. I come up Healdsburg Avenue and it’s the redwood trees in the new park around the Mill District and the ones in the plaza that are punctuating the built-scape, which is unique. It’s part of the language here from a landscape standpoint.

When you get down to the pedestrian level, what goes into making this successful in a city like Healdsburg?

JAMES MUNDEN: Landscape is only as good as it’s maintained. There’s a certain amount of pruning and effort that goes into creating a landscape and maintaining it. It’s a little bit more relaxed here and things aren’t pruned as tight. A little bit more floppy, a little bit more rough around the edges.

LUCAS DEXTER: If you go to other neighborhoods like Atherton, Danville or to the East Coast, you have neighborhoods that are clipped tight, making sure you’re as good as your neighbor. Maybe there’s a little bit of that here downtown, but I think when we get into the rural areas, it’s much more about a natural flow.

JAMES MUNDEN: From a design standpoint, I really love when there is a natural flow with having that wild feeling in an area that can be contained and that may spill out again somewhere else. The combination of the linear vines mixed with the rolling hills is compelling & romantic.

JIM HEID: Your traditional English garden, a little cottage garden, looks naturalized and wild, but is a highly manicured landscape.

JAMES MUNDEN: Yes, manicured but also there’s a very pastoral, rustic element which is a reaction to the French Versailles, linear aesthetic.

How does landscape architecture + design contribute to the reciprocal relationships we have with the land?

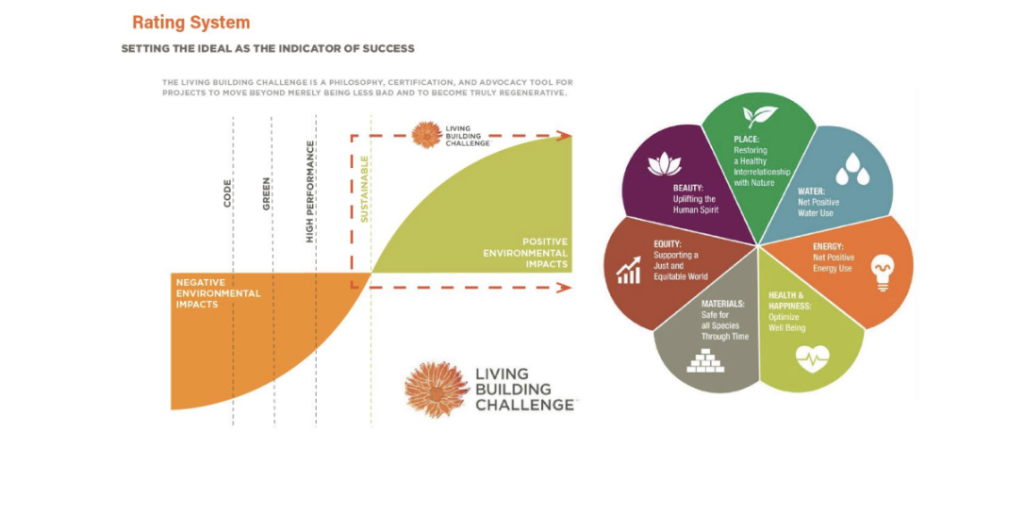

JAMES MUNDEN: Working on a project like Silver Oak, they had such high ideals to achieve the Living Building Challenge Certification (LBC) and LEED Platinum Certification.

There are many certifications out there, but the LBC is one that is really pushing the boundaries to be more of a philosophy and less about ticking boxes. It’s inspiring people to hit a certain standard that, honestly, is pretty hard to get to, but they’re okay with that. There’s a lot of landscape architects and architects who are trying to go for this certification, and they didn’t quite make it but the LBC is encouraging the effort more than anything. As long as you’re trying to push the envelope and bring everyone along.

They have a ranking system modeled off of 7 petals. The first is about the place and restoring a healthy interrelationship with nature. The second is about water and energy, being net positive and trying to keep that closed loop system. Health and happiness is another petal which other certifications don’t talk about as much but are key in creating a regenerative project.

Equity and beauty are two other petals. I think you’ve mentioned before, Jim, beauty is one of those fuzzy terms.

JIM HEID: Yeah. Squishy.

JAMES MUNDEN: I think it’s important to talk about beauty because it is uplifting to the human spirit and creates a reason to protect the land. Equity is a really critical element, especially in our current climate, making sure that areas are just, accessible and representative of the community it serves. The last one is materials. The materials we use have a huge impact. Once they’re in the ground, they can start to degrade and cause more problems for the ecosystem in the future. Making sure materials are not on the ‘red list’, means less chemicals and less oil-based products. This is certainly an area ripe for innovation. The LBC is helping to push the profession forward.

We’ve talked a little about how agriculture has evolved over time and now we are starting to see farming practices, not only vineyards, looking at the bigger picture. They’re looking at the ecology, soil health and planting choices.

I know a lot of the many great landscape architects in the Bay Area are trying to educate clients on the benefits of using, not just ornamental plants, but plants that contribute to the ecosystem. Perhaps they attract the right insects that eat the pests that would normally be eradicated by pesticides.

The cover crops are another key planting strategy that brings nutrients back into the soil after harvest. When you drive through the vineyards, you’re going to see all the mustard, lupins, legumes and nitrogen fixers that protect the earth in between the growing seasons.

Credit: MFLA

If one can start to integrate things that are beautiful, but also have a regional purpose, it could be something that spreads into the Healdsburg city center more. Like the question you posed earlier, Jim, about how the city could start to take on a more regional Sonoma County quality. The early land management techniques executed by tribes, like the Western Wappo and Dry Creek Pomo, are not just happening on the vineyard, it’s spreading to other types of farms and communities. When you come up here, this approach could help distinguish the vernacular from city to city, evolving with the practices.

JIM HEID: And it’s not only about beauty but, hopefully, there’s some education around why certain plants are better for that local ecology or for the soil because they are performing an ecosystem service.

JAMES MUNDEN: You’re right. Education, awareness and talking about it more and more, just like we are today, is important.

This leads me to let Lucas talk more about some of the great work he’s been doing around experimentation with plants and making room for that experimentation for the benefit of design + agriculture.

The example of being able to treat water with a bioreactor, like they did at Silver Oak, or using the byproduct of grape skins post crush as a compost and mulch are all examples of positive experimentation in the wine industry. So, the more you start to push the boundaries and be open to ideas, the more these happy accidents can happen. As designers, contractors and people within our industry keep sharing these experiments, the culture of being open to different ways of doing things creates a more biodiverse environment.

LUCAS DEXTER: Of course we want to design with drought tolerant plants that don’t need all this extra effort, water and maintenance. But we’re limited to a certain palette of what’s available.

Is everybody familiar with the plant, Lil Ollie? Little ollie. It’s not a rapper from LA. (audience laughs)

It’s a dwarf olive that was found as a witch’s broom in an olive tree, and it was grafted onto its own rootstock. From it, we now have this little bush which, at it’s largest at 25 years old, can get up to 4-5ft. They’re a fantastic solution because it’s a drought tolerant, really tough plant, that we can use in our landscape. It’s not from the area on the West Coast or from the Americas, but it’s a nice solution for our regional climate needs.

If we had native plants to be a wonderful drought tolerant evergreen hedge, that would be great, but we are limited to what is available. We have a Toyon and coffee berry as native hedge material but nothing that replaces a box hedge style, so I’m working on that.

The witch’s broom (center image above), which is a mutation, I actually found in a big bay tree we have around here called Umbilaria Californica.

We took 250 cuttings from it, and we’re growing them with Devil Mountain Nursery right now. We’re hoping to create a native California boxwood replacement or an alternative evergreen hedge that could thrive in sand or clay and loves the Sonoma + Napa County environment.

JIM HEID: How did you find it? Were you just driving by and saw the tree?

LUCAS DEXTER: Yeah, I was driving and I have really good pattern recognition that I have learned to lean into. It started when I saw a documentary about the Franciscan Manzanita and this gentleman was driving across the bridge right when they started construction on the Presidio side of the Tunnel Top project in 2010. From the corner of his eye, in the median where the excavator was, he thought it looked like a manzanita he saw in a textbook that’s supposed to be extinct, called the Franciscan Manzanita. Sure enough, it was this supposedly extinct plant, and they create this whole operation to dig it and put it in a secret location. I’m watching this documentary and I’m thinking, if 70,000 people drive past this thing for over 100 years, and this guy is the first person to notice it, then this Oak Tree on the Silverado Trail in Calistoga that I drive by every day for years is definitely unique too. So I took a video of me with this oak tree and sent it to the International Oak Society. They called me about 5 minutes later and asked where I was and that they’d never seen it before. So we did genetic testing at the David Ackerley lab at UC Berkeley, and I got it named and published, Quercus Douglasii, Dexter’s Blue. It’s a dwarf blue oak.

Now we can have a dwarf blue oak in our gardens that, you know, tops out at 14 feet which opens up new possibilities for design.

To have these native California plants that can exist here on minimal effort, because this is their native habitat, advances us in the right direction. So, I’m really pushing to get these plants developed in the trades.

Pictured: Craftwork Healdsburg. Photo credit Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

JIM HEID: Tell us about the idea of planting, not what’s native to here, but what is native many miles south of us.

LUCAS DEXTER: Yeah. About 10 years ago, I heard about this concept from David Muffley of Oaktopia.com. I thought initially the guy was just crazy, because he was telling people not to plant natives in your area but natives that are south of you. So he’s been pushing for us to plant Mexican Oaks and Island Oaks from South of California because of his idea that with climate change progressing as it is, we’re going to have a climate similar to Mexico in the future. I thought that was really interesting, but I thought he was crazy until I evacuated from 7 different fires since then. I’m realizing he might be onto something because things are changing so quickly, so I’m coming around to the idea.

JIM HEID: Can you quickly tell us about the book you’re in?

LUCAS DEXTER: Yes of course. So, with these new plant introductions I’ve been involved in and having a social media presence, Amy Stewart, the author of ‘The Drunken Botanist’, reached out to me about a book she wanted to create on tree collectors. She included me in a chapter and actually illustrated the book with a portrait of me. It’s a total honor and it came out in June. It’s really just changed my life since it’s got a lot of attention, including a New York Times piece, which was big.

JIM HEID: So, it’s you and other tree collectors in there?

LUCAS DEXTER: Yes, there’s fifty of us in the book. My story is probably the least interesting in the book. There are some really interesting stories in there, so I highly suggest picking it up and taking a look. The audiobook is great too because the chapters are only 5 minutes long. 50 chapters of 50 people. It’s a book you can pick up on any chapter and they’re all unique stories.

JAMES MUNDEN: Thanks Lucas. I think it’s a nice place to end on because there is hope there with what you are doing, especially in regards to fire which is obviously a very destructive component of our lives here.

Lucas, appreciate you being part of the conversation. It has made our chat a lot more rich and helped to highlight the importance of an open exchange of knowledge + curiosity within our industry.

Jim, thanks for hosting and helping to organize this.

JIM HEID: Thank you!

Pictured: James Munden, Lucas Dexter and attendee Hani Hong. Photo credit: Rob Villanueva rvsf.co

Audience Questions:

JIM HEID: We have time for 1 or 2 questions or comments from the audience and then we’ll hang around to chat to everyone.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: This question is for Lucas. What nurseries are you collaborating with in your work?

LUCAS DEXTER: Yeah. Great question. I don’t have my own nursery but I have a personal collection in a nursery.

So when I first started working with the oaks, I found out very quickly that you can’t graft oaks which is the only way to replicate the genetics. A seedling, wouldn’t cut it because it’s a roll of the genetic dice. So I searched for someone who has a grafting operation with oaks, and there’s really only one company that did it in scale. Heritage Liners and Seedlings in Oregon have a hot pipe system where they lay down the graft union into this continuous pipe that blows hot air, and it keeps the graft union dry. It was developed by Oregon State University. I used them, which was great, but they only sell liners as wholesale to other larger nurseries and I really wanted to get in when the plants were larger because there are benefits for that.

I work with Devil Mountain Nursery in my day job for purchasing plants for installations, so I got to know them really well, told them about this work, and then moved all my oak operations to them. They also currently have a variegated redwood that I’m doing with them. I’m exclusively with Devil Mountain now except for a variegated maple which I grow with Mendocino Maples.

JIM HEID: Thanks for coming. Please stick around for some Silver Oak Cellars wine.

Thank you to our speakers, supporters, collaborators and sponsors: MFLA, Dexter Estate Landscapes, Craftwork and Silver Oak Cellars Wine. Special thanks to Amber Munden.